How to Avoid Sugar

By: Anne Zauderer, DC

If you had read the title of this article to our ancestors 10,000 years ago, you would have sounded crazy. Avoid sugar? Our ancestors’ survival was dependent upon finding energy (food) and, in nature, sugar is the best source of quick energy. This is why sugar tastes so good to us. It is genetically programmed in our brains to signal pleasure and reward. In fact, our brains run on sugar (glucose) for energy. Our brains use about 20% of our daily energy intake, despite the fact that the brain comprises only 2% of our body’s weight.

As with any substance, a little bit can be good, but too much can be toxic. Water is necessary for our survival, but you can overconsume it or “hyperhydrate” and throw your electrolytes out of balance enough to cause death. Sugar is the same way. Our bodies are dependent upon glucose for survival. However, overconsumption of sugar has been implicated in many of the chronic diseases of modern living that we see today.

Overconsumption

We are a nation that is addicted to sugar. As mentioned above, we have a biological need and desire for sugar. As our society has become more modernized, sugar is more available and therefore we consume more.

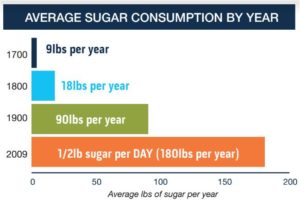

- In 1700, the average person consumed about 4 pounds of sugar per year.

- In 1800, the average person consumed about 18 pounds of sugar per year.

- In 1900, individual consumption had risen to 90 pounds of sugar per year.

- In 2009, more than 50 percent of Americans consumed 1/2 pound of sugar per day, which is 180 pounds of sugar per year.

These statistics are astonishing! We are literally eating our body weight in sugar every year. Most people are aware of the health hazards of consuming too much sugar, so why do we continue to do it? Are we just slaves to our primal desire for sugar? I don’t think that’s the whole story.

Hormones

Our more distant ancestors, because they did not have the modern conveniences we have today, spent a lot of time and energy hunting and foraging for food. Their survival was dependent on the available food. This pattern of “feast and famine” helped shape our biochemistry. Food was a communication between the environment and the physiology of humans. The availability of food (energy) would dictate certain hormonal responses in the body.

For instance, our fat cells release a hormone called leptin, which is the signal to the body that we have adequate storage of energy (or fat). When leptin is released, that suppresses our appetite. If we have adequate storage, there’s no need to eat more. Ghrelin is the opposite of leptin, it signals us to tell us when we are hungry. Too much ghrelin can lead to over-eating.

These hormones don’t just affect our hunger, they also have systemic effects because, as mentioned above, the availability of food was essential for our ancestors. Leptin also has an effect on our reproductive and thyroid hormones. If body fat drops below a certain percentage and leptin is not released, that signals the body to downregulate reproductive hormone production. (This is the reason why women who are very lean and athletic very often don’t have a menstrual cycle.) If our ancestors did not have availability of food, that was not a good time to reproduce.1 In addition, when leptin levels are low, this signals the thyroid to slow down2 because when food is not available, this is not a good time to be metabolically active.

These hormones don’t just affect our hunger, they also have systemic effects because, as mentioned above, the availability of food was essential for our ancestors. Leptin also has an effect on our reproductive and thyroid hormones. If body fat drops below a certain percentage and leptin is not released, that signals the body to downregulate reproductive hormone production. (This is the reason why women who are very lean and athletic very often don’t have a menstrual cycle.) If our ancestors did not have availability of food, that was not a good time to reproduce.1 In addition, when leptin levels are low, this signals the thyroid to slow down2 because when food is not available, this is not a good time to be metabolically active.

However, in the modern world, we have a different kind of leptin problem. We are over-consuming sugar (especially fructose) at such high levels that we are developing leptin-resistance. This is similar to insulin resistance, and in fact the two seem to share signaling pathways and, therefore, go hand-in-hand. This means that we are releasing so much leptin that our brains stop listening to it. So we end up with all of the effects of low leptin: low thyroid function and metabolism, low production of reproductive hormones, decreased energy, and increased fat storage; yet, we are still consuming more calories than our bodies can use. There is no decrease in hunger and no increase in metabolism, which leads to feelings of starvation and increased appetite. A vicious cycle ensues:

- You eat more (especially sugar), gain body fat.

- More body fat means increased leptin release from fat cells.

- Too much fat means that proper leptin signaling is disrupted (leptin-resistance).

- Your brain thinks you are starving, which makes you want to eat more.

- You gain more fat and get hungrier.

- You thyroid starts to down-regulate (hypothyroidism) and you feel tired, you eat more and gain more fat.

- The cycle continues.

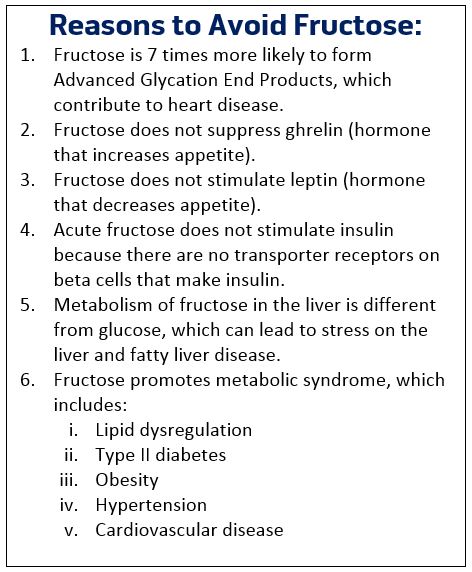

A very important piece to this puzzle is a type of sugar called fructose. Fructose has been shown to induce leptin resistance3 and does not suppress ghrelin. Therefore, fructose is a major contributor to the cycle of obesity. Why is this significant? Since prior to World War II, we have more than tripled the amount of fructose we are consuming.

Fructose vs. Glucose

Fructose and glucose are both simple sugars, also known as monosaccharides. Even though  they are both sugars, they are metabolized by the body very differently. Whereas glucose can be readily absorbed for energy, fructose has to be broken down by the liver. Only about 25% of the fructose you eat can be used as energy (in the liver), the other 75% is stored as fat. Therefore, metabolically, the purpose of eating fructose is for fat storage. Again, going back to our ancestors, this makes sense. They primarily consumed fructose during the season when fruits were ripening. This allowed them to store up energy (as fat) for the winter.

they are both sugars, they are metabolized by the body very differently. Whereas glucose can be readily absorbed for energy, fructose has to be broken down by the liver. Only about 25% of the fructose you eat can be used as energy (in the liver), the other 75% is stored as fat. Therefore, metabolically, the purpose of eating fructose is for fat storage. Again, going back to our ancestors, this makes sense. They primarily consumed fructose during the season when fruits were ripening. This allowed them to store up energy (as fat) for the winter.

This is a pretty brilliant design by the body to protect us from starvation. However, this system was designed for sugars that existed in whole foods, such as fruits. Whole foods contain fiber and nutrients that help us process the sugars in them. In the modern diet we have stripped away all of the fiber and refined sugars down to a form that is more quickly and easily absorbed by the body. Because of this delivery system, we are able to consume a greater quantity of sugar in one sitting.

How to Avoid Sugar

To break the hormonal cycle described above, we have to eliminate processed sugar and processed foods from our diet as much as we can. Go on a 60-day “sugar fast” and avoid all added sugar. Some of the biggest culprits for over-consumption of sugar are: soda, sports drinks, desserts, and convenience foods. We know we should avoid most of these foods. However, there is also a lot of hidden sugar in foods that we wouldn’t necessarily think to avoid, and these foods really add to our daily sugar intake. Some of these foods to watch out for are: peanut butter, tomato sauces, yogurt, granola bars, protein bars, coffee drinks, juices, dried fruits, condiments (ketchup, BBQ sauce, salad dressing), and certain alcoholic beverages.

Eliminating sugar (especially fructose) is the best first step. Here are a few other strategies to help reset leptin resistance:

- Increase consumption of healthy fats (avocados, coconut oil, MCT oil, nuts and seeds, grass-fed meat and eggs). This also includes adding a supplement of Omega 3 fatty acids.

- Limit carbohydrate consumption in the morning and afternoon (our body is more insulin-sensitive after 3:00pm).

- Utilize intermittent fasting.

- Manage stress levels (good quality sleep, exercise and movement).

- Avoid toxins in cosmetics, cleaning products, water, air and food.

For more information, join Dr. Anne for a lunchtime lecture at the Riordan Clinic, Wichita campus, on Wednesday, April 19th at noon, where she discusses, in more detail, the effects of sugar in the diet and how it connects to many modern, chronic diseases.

References:

- Chou SH, Mantzoros C. 20 Years of Leptin: Role of leptin in human reproductive disorders. J Endocrinol October 1, 2014 223 T49-T62.

- Flier JS, Harris M, Hollenberg AN. Leptin, nutrition, and the thyroid: the why, the wherefore, and the wiring. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;105(7):859-861.

- Shapiro A, Mu W, Roncal C, Cheng KY, Johnson RJ, Scarpace PJ. Fructose-induced leptin resistance exacerbates weight gain in response to subsequent high-fat feeding. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol.2008. 295 (5): R1370–5.